September 2024

Volume 4

Part 6 - The refurbishment of Grenfell Tower

HC 19–IV

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 4 September 2024

This report contains content which some may find distressing.

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at contact@grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk.

ISBN 978-1-5286-5080-9

(Volume 4 of 7)

E03165832 09/2024

The refurbishment of Grenfell Tower between 2012 and 2016 lies at the heart of our investigations. We have therefore examined in some detail the course of the project from its original inception to completion. In order to provide the context in which the important decisions were made we begin with a description of the regulations and guidance relating to the construction of external walls of high-rise buildings which ought to have been uppermost in the minds of those making decisions about the nature of the work to be undertaken and the choice of materials.

That is followed by a brief description of the people and organisations involved in the work, which we have included to give the reader an overall understanding of the way in which individuals and organisations that appear frequently in the following chapters fit into the overall picture.

The story of how the refurbishment was planned and the important roles filled is of interest and importance, not only because decisions were made at that stage that affected the subsequent course of the work, but also because it sheds light on the way in which the TMO, as the client for the refurbishment, went about managing its own responsibilities.

Expert advice on fire safety was sought in the form of a fire safety strategy for the building, both in its existing form and following its intended refurbishment, but for reasons we describe, the latter was never completed, leaving a significant gap in the advice that should have been received by the TMO and the design team. A failure to understand the characteristics of the materials proposed for use in the refurbishment turned out to have disastrous consequences.

There follow several chapters in which we describe how the various materials and products used in the work came to be selected. It is a subject that calls for detailed examination because it was the decision to use aluminium composite panels with unmodified polyethylene cores in what was known as “cassette” form as the rainscreen that was primarily responsible for the rapid spread of the fire. Other products made a contribution, however, in particular the Celotex and Kingspan insulation boards, neither of which complied with the guidance on the use of combustible materials on high-rise buildings.

The requirement to obtain building control approval for the refurbishment should have ensured that any errors in design or the choice of materials were identified and put right before the work started. Regrettably, however, that did not happen. Given the importance of building control for the protection of the public, we have examined in some depth the reasons why the system failed to achieve the purpose for which it was designed.

Our investigations have disclosed that errors were made by many of those involved in the refurbishment and at many points during its course. As a result, we have found it convenient to collect our criticisms of each of the organisations principally responsible for the work in a number of individual chapters at the end of this Part.

Chapter 5 of the Phase 1 report contains a brief summary of the main legislative provisions and associated guidance that applied to the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower. However, in order to give a true picture of the context in which important decisions were taken in connection with the work, it is necessary at this stage to describe those provisions more fully and in greater detail. Given the important role played by the cladding system in the fire at Grenfell Tower, we concentrate on the statutory framework, including the statutory guidance relating to the construction of external walls, applicable during the period in which the refurbishment was carried out. In this chapter we also examine briefly the regulatory framework governing building control and the duties applicable under the CDM Regulations.

The Building Act 1984 (“the Act”)[1] is the principal primary legislation governing building and buildings and related matters. Section 1(1) of the Act gives the Secretary of State the power to make regulations with respect (among other things) to the design and construction of buildings for a number of purposes, including securing the health, safety and welfare of persons in or about buildings. Regulations made under section 1(1) of the Act are known as “building regulations” and were made by way of statutory instrument. The regulations in force at the time of the refurbishment were the Building Regulations 2010 (“the Regulations”).[2]

Section 6 of the Act provides that the Secretary of State, or a designated body, may approve and issue documents for the purpose of providing practical guidance with respect to the requirements of any provision of the Regulations. At the time of the refurbishment that practical guidance was contained in a series of Approved Documents. The provisions of the Approved Documents are not mandatory; their purpose is merely to describe one or more ways in which the requirements of the Regulations can be met. Failure to comply with an Approved Document does not in itself render a person liable to any civil or criminal proceedings, but it may be relied upon in any proceedings as “tending to establish liability”. Likewise, compliance with the provisions of an Approved Document, although not proof of compliance with the Regulations, may be relied on in any proceedings as “tending to negative liability”.[3] It is important to note, however, that compliance with the Approved Documents does not ensure compliance with the Regulations.

Schedule 1 of the Act sets out further matters which building regulations may provide for. Paragraph 7 of Schedule 1 provides that they may make provision for (among other things) fire precautions.[4]

Part 3 of the Regulations contains requirements for local authorities to be notified of building work. In particular, regulation 12(3) obliges a person intending to carry out building work in relation to a building to which the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 (the Fire Safety Order) applies to deposit full plans with the local authority in accordance with regulation 14. (The refurbishment of Grenfell Tower involved work on a building to which the Fire Safety Order applied and a deposit of full plans was therefore required.) By virtue of regulation 14, full plans are to consist of a description of the proposed work together with plans describing the work and demonstrating that it would comply with the Regulations.

The Act itself provides for the local authority’s response to the deposit of full plans. Section 16 provides that, where plans for proposed work are deposited with a local authority, it is their duty to pass the plans unless a provision elsewhere in the Act requires them to be refused, or the plans are defective, or they show that the proposed work would contravene any of the Regulations. If the plans are defective or show that the work would contravene the Regulations, the local authority may reject them or (with the consent of the person by whom they were deposited) pass them subject to conditions. Within 5 weeks from the deposit of plans the local authority must give notice to the depositor stating whether they have been passed or rejected.[5]

Failure to comply with the Regulations is punishable by a fine (section 35), but in addition local authorities have the power to require the owner of the building to pull down or remove any work that contravenes the Regulations or make such alterations to it as are necessary to make it comply with them (section 36).

The Regulations prescribe the standards that building work must meet and impose on the person proposing to carry it out a requirement to obtain approval from a local authority or approved inspector. The requirements for building work are set out in regulation 4, which provides that building work shall be carried out so that it complies with the requirements contained in Schedule 1. The Regulations apply to building work as defined in regulation 3, which includes, among other things, the material alteration of an existing building. An alteration is material for these purposes if the work, or any part of it, would at any stage result in the building’s ceasing to comply with any one of a number of listed requirements of the Regulations or (if it did not comply with such a requirement before the work commenced) becoming more unsatisfactory than it previously had been, but there is no requirement when work is done to an existing building to bring it up to current standards. This is sometimes known as the “non-worsening principle”. The listed requirements include functional requirements B1, B3, B4 and B5 relating to fire safety.[6] It is not disputed that the cladding work to Grenfell Tower, including the addition of insulation, and the renovation of the smoke control system constituted material alterations and that the Regulations therefore applied to them.

Paragraph 8(1)(e) of Schedule 1 to the Act gives the Secretary of State power to make building regulations with respect to buildings that are subject to a material change of use. A material change of use is defined in regulation 5. It occurs when, among other things, a building which contains dwellings is altered to contain a greater or lesser number of dwellings than it did previously. In the case of Grenfell Tower refurbishment, the addition of new flats in those parts of the building that had previously been put to other uses constituted a material change of use.

The prescribed standards for building work are expressed in schedule 1 to the Regulations in terms of functional requirements. Although the refurbishment was required to comply with all the requirements, for the purposes of this report we concentrate on Part B.

Part B is concerned with fire safety and is divided into five sections:

B1 Means of warning and escape.

B2 Internal fire spread (linings).

B3 Internal fire spread (structure).

B4 External fire spread.

B5 Access and facilities for the fire service.

Requirements B1, B3(4) and B4 are of particular relevance to the fire at Grenfell Tower and deserve to be quoted in full:

B1. The building shall be designed and constructed so that there are appropriate provisions for the early warning of fire, and appropriate means of escape in case of fire from the building to a place of safety outside the building capable of being safely and effectively used at all material times.

B3. (4) The building shall be designed and constructed so that the unseen spread of fire and smoke within concealed spaces in its structure and fabric is inhibited.

B4. (1) The external walls of the building shall adequately resist the spread of fire over the walls and from one building to another, having regard to the height, use and position of the building.

(2) The roof of the building shall adequately resist the spread of fire over the roof and from one building to another, having regard to the use and position of the building.

The Regulations also contain certain energy efficiency requirements. In particular, regulation 23 provides that where renovation of a thermal element (which would include an external wall) constitutes a major renovation or amounts to the renovation of more than 50% of the element’s surface area, the renovation must be carried out so as to comply with paragraph L1(a) of schedule 1 in so far as that is technically, functionally and economically feasible. Requirement L of schedule 1 is headed “Conservation of Fuel and Power” and paragraph L1(a) provides that reasonable provision shall be made for the conservation of fuel and power in buildings by limiting heat gains and losses through thermal elements and other parts of the building fabric.

The supervision of the proposed work by the local authority is intended to culminate in the issue of a completion certificate evidencing compliance with certain requirements of the Regulations. Those requirements include the applicable requirements of regulation 38 (discussed below) and schedule 1 of the Regulations. Once issued, a certificate is evidence (but not conclusive evidence) that the requirements specified in the certificate have been complied with.

Regulation 38 is concerned with the provision of fire safety information. It applies where building work consists of or includes the erection or extension of a relevant building or is carried out in connection with a relevant change of use and when Part B of Schedule 1 imposes a requirement in relation to the work. In those circumstances the regulation obliges the person carrying out the work to give the responsible person under the Fire Safety Order not later than the date of completion of the work or the date of occupation of the building or extension, whichever is the earlier, information relating to the design and construction of the building and the services, fittings and equipment provided in or in connection with it that will assist that person to operate and maintain the building with reasonable safety.

The Fire Safety Order is considered in greater detail in Part 2 of this report. For the purposes of the Regulations, however, it is important to note that article 45 requires a local authority in receipt of a full plans application in relation to a building to which the order applies to consult the enforcing authority (in this case the London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority (“LFEPA”) before passing the plans.[7]

The Construction (Design and Management) Regulations were made by the Secretary of State under powers in the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. They seek to protect persons against risks to health and safety arising from construction work through the establishment of a systematic framework for the assessment and management of those risks. The definition of construction work includes the construction, alteration, conversion, fitting out, commissioning, renovation, repair, upkeep, redecoration or other maintenance of any building.[8] The first regulations were made in 1994 and came into force in March 1995. They were replaced in 2007 and again 2015. The 2007 Regulations remained in force until 5 April 2015 when the 2015 Regulations came into force.

The CDM Regulations 1994 and 2007 were each supported by guidance in the form of Approved Codes of Practice (ACOPs) published by the Health and Safety Executive, which provided practical guidance on how to comply with the law.[9]

When the CDM Regulations 2007 were superseded by the CDM Regulations 2015, a transition period from 6 April to 6 October 2015 was introduced to enable all those affected to put in place alternative arrangements.

The CDM Regulations 2007 are relevant to our investigation of the refurbishment because they imposed various duties on clients, designers (defined as including anyone preparing or modifying a design or instructing others to do so)[10] and contractors relating to health and safety or reinforced existing duties under health and safety legislation. We refer to these in more detail where relevant in the following chapters describing the refurbishment work at Grenfell Tower. The 2015 Regulations also imposed an obligation on the principal designer to prepare a health and safety file, keep it under review and deliver it to the client at the end of the project.[11]

As we have set out above, section 6 of the Building Act 1984 Act provides for the publication by the Secretary of State of documents providing practical guidance with respect to the requirements of the Building Regulations. At the time of the refurbishment that practical guidance was contained in a series of Approved Documents, which themselves referred to British Standards and other guidance. Approved Document B dealt with fire safety. Before the Grenfell Tower fire, it was divided into two volumes: volume 1 dealt with dwelling houses; volume 2 dealt with all other buildings, including blocks of flats and buildings containing flats.

As we have set out in Chapters 4 and 6, Approved Document B was first published in 1985 and was amended on numerous occasions thereafter. In this section of the report we have referred to the 2006 version incorporating the 2007, 2010 and 2013 amendments.[12]

Section 12 of Approved Document B provided guidance on the construction of external walls.[13] Our attention has focused most closely on paragraphs 12.5–12.8 of that guidance, which are worth setting out in full:

“12.5 The external envelope of a building should not provide a medium for fire spread if it is likely to be a risk to health or safety. The use of combustible materials in the cladding system and extensive cavities may present such a risk in tall buildings.

External walls should either meet the guidance given in paragraphs 12.6 to 12.9 or meet the performance criteria given in the BRE Report Fire performance of external thermal insulation for walls of multi storey buildings (BR 135) for cladding systems using full scale test data from BS 8414-1:2002 or BS 8414-2:2005.

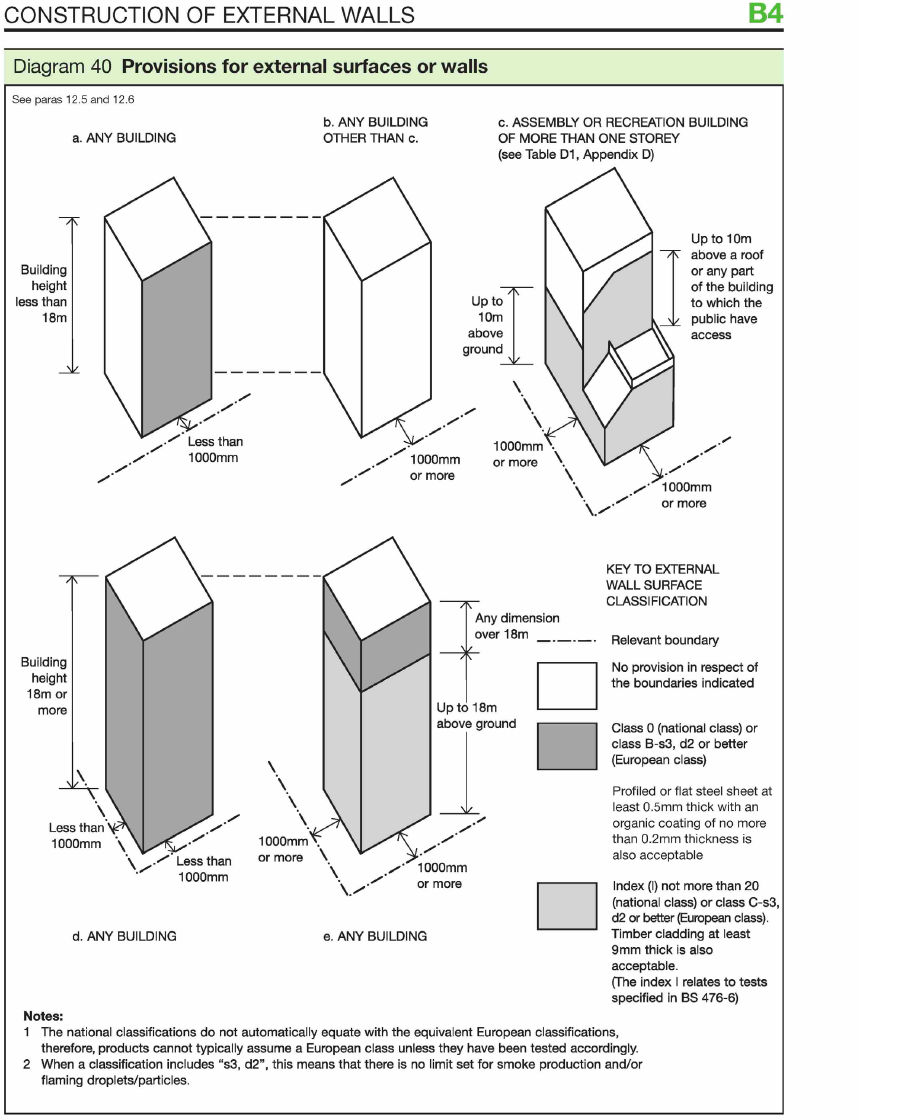

12.6 The external surfaces of walls should meet the provisions in Diagram 40…

12.7 In a building with a storey 18m or more above ground level any insulation product, filler material (not including gaskets, sealants and similar) etc. used in the external wall construction should be of limited combustibility (see Appendix A). This restriction does not apply to masonry cavity wall construction which complies with Diagram 34 in Section 9.[14]

12.8 Cavity barriers should be provided in accordance with Section 9.”

Paragraph 12.5 thus provided two potential routes to compliance with the Regulations: following the guidance in paragraphs 12.6 to 12.9 (sometimes referred to as the “linear route”) or meeting the performance criteria in BR 135 following testing in accordance with BS 8414. However, Approved Document B provided no more than guidance and in addition to the two routes it set out, there could be other ways of demonstrating compliance with the functional requirements of the Regulations to which we refer below. We note in passing that the majority of witnesses who gave evidence about the design of the Grenfell Tower refurbishment either thought that the “linear route” had been adopted or were not aware which route had been adopted.[15]

Paragraph 12.6 of Approved Document B provided that the external surfaces of walls should meet the provisions in Diagram 40.[16]

The heading of Diagram 40 (in particular the use of the words “or walls”) might suggest that a distinction is being drawn between “external surfaces” and “walls” but the label in the key to Diagram 40 is concerned solely with “external wall surface classification”. We think it is clear that it was intended to apply to the wall’s external surface and thus to the material or product that makes up the outer surface of the wall.[17] That is certainly consistent with the language of paragraph 12.6 of the guidance which introduces Diagram 40 and which refers to the “external surfaces of walls”.

Diagram 40e applied to Grenfell Tower and required that above 18 metres from the ground the external surface of the walls had to satisfy national class 0 or European class B-s3, d2 or better. We have described in Chapter 5 the tests which supported those classifications.

In our view the wording of paragraph 12.6 suggests that it applies to the external surface of a wall and does not include any product, such as insulation, that may have been fitted behind it. Similarly, when considering a composite product, such as an ACM panel, the paragraph naturally refers to its surface rather than to its core.

Paragraph 12.7 is headed “Insulation Materials/Products”. It provided that in a building with a storey 18 metres or more above ground level any insulation used in the external wall construction should be of limited combustibility.[18] Limited combustibility is defined in Appendix A of Approved Document B (see Chapter 6).[19]

It has been argued that paragraph 12.7 should be understood as applying to the core of ACM cladding panels of the kind installed at Grenfell Tower.[20] The argument was put in two ways. The first relied on the use of the word “filler” in paragraph 12.7, which was said to be apt to refer to the core of a composite cladding panel. We do not agree with that. The word “filler” forms part of the expression “insulation product, filler material (not including gaskets, sealants and similar) etc. used in the external wall construction”. In that context the word “filler” naturally means a material, such as compressible fibre or expanding foam, used to fill gaps of an unplanned or occasional kind rather than small apertures that are intended to be closed off by gaskets or sealants. It is not apt to refer to the core of a composite cladding panel which is an integral part of the finished product. We derive further support for our conclusion from the fact that we have not seen any evidence that the core of a composite panel was described as “filler” by anyone in the building industry before the Grenfell Tower fire.

The second argument was that the provisions relating to external surfaces in paragraph 12.6 and Diagram 40 were additional to the basic requirement that the external walls of a building over 18 metres in height should be composed only of materials of limited combustibility in the facade and do not override the functional requirement that they adequately resist the spread of fire.[21] That interpretation was supported by Beryl Menzies[22] and support can also be found for it in industry guidance published by the Building Control Alliance in its Technical Guidance Note 18, which we discuss in Chapter 49.[23] However, in neither case was any reason given for adopting that interpretation, beyond saying that it would give effect to functional requirement B4(1).

We do not agree that paragraph 12.7 of Approved Document B can be read in that way. Functional requirement B4(1) sets out the standard with which external walls must comply. The purpose of Approved Document B was to provide guidance on ways in which that standard might be met, which it did by identifying certain elements of the wall and suggesting the kinds of materials that were likely to ensure compliance. There is nothing in the language of paragraphs 12.5–12.9 (including paragraph 12.7) to support the conclusion that all elements of the external wall, including the core of any composite panel, should be of limited combustibility. The only reference to “limited combustibility” is found in paragraph 12.7 which referred only to insulation products. That would naturally have been understood as referring to materials and products used for the purposes of insulation, not as referring to materials chosen for other purposes but which happen to have insulating properties.

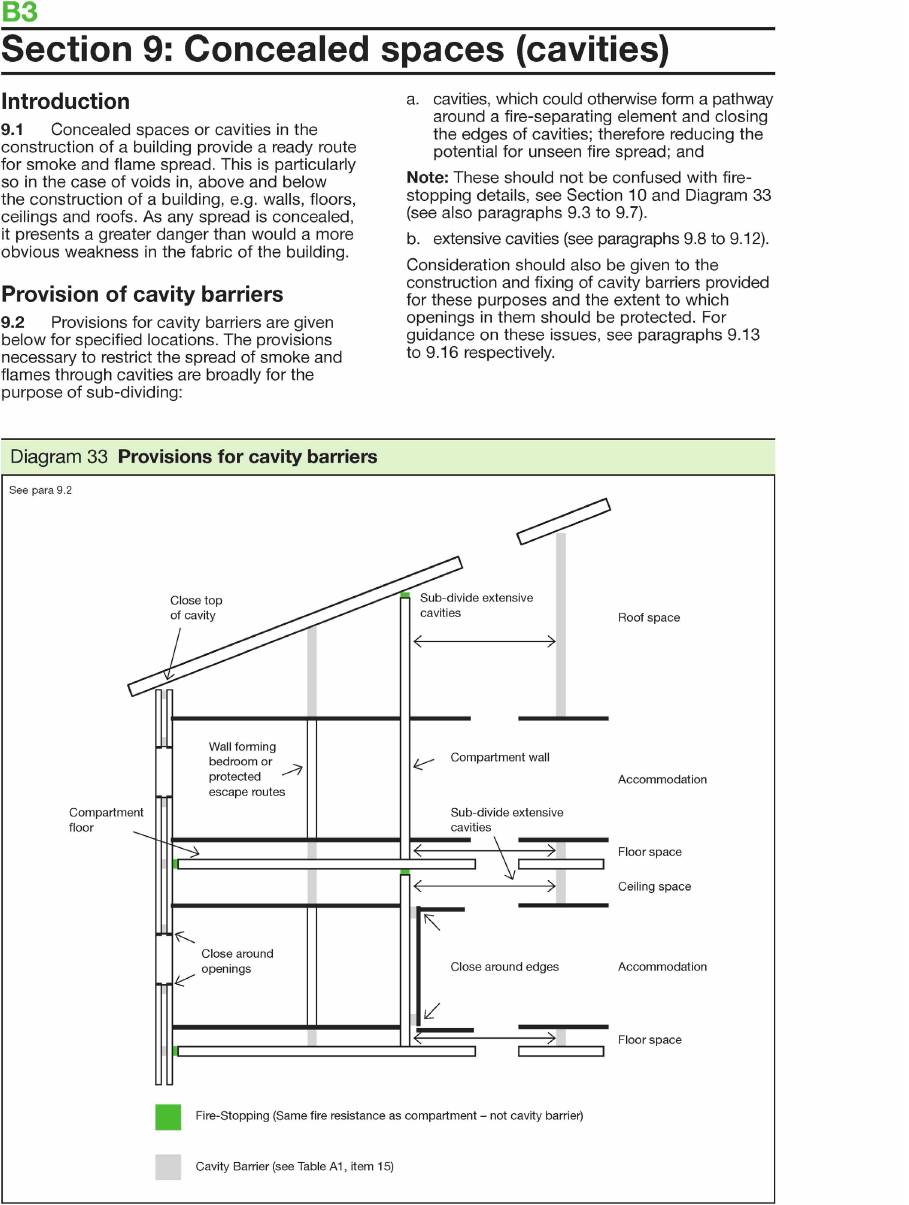

Section 9 of Approved Document B provided guidance on the provision of cavity barriers to inhibit the spread of smoke and flame through concealed spaces or cavities in the construction of a building as required by functional requirement B3.[24] Paragraph 9.1 draws attention to the risks of fire spread within cavities and warns that “as any spread is concealed, it presents a greater danger than would a more obvious weakness in the fabric of the building.”[25] Paragraph 9.3 makes it clear that cavity barriers should be provided to close the edges of cavities, “including around openings”. Diagram 33 (reproduced below) shows where cavity barriers are required in external walls, namely, at the lines of compartment floors and compartment walls, at the top of any cavities in the walls and around openings such as those provided for doors and windows.

Paragraph 9.13 gives guidance on the construction and fitting of cavity barriers and states that they should provide at least 30 minutes’ fire resistance.[26] Cavity barriers should be distinguished from fire stopping, which is a seal provided to close an imperfection of fit or design tolerance between elements or components, to restrict the passage of fire and smoke.[27]

Our investigations have revealed two particular problems relating to Approved Document B to which we think we should draw attention. The first relates to the guidance itself. Paragraph 2.3c on the means of escape from flats assumes that compliance with functional requirement B3 will provide a high degree of compartmentation and a low probability of fire spreading beyond the flat of origin, so that simultaneous evacuation of the building is unlikely to be necessary. In other words, it assumes that there would be no need for a partial or total evacuation of the building in the unlikely event that the fire spread beyond the compartment of origin and that a stay put strategy is therefore appropriate. That assumption holds good, however, only as long as the external wall of the building does not itself support the spread of fire.

Some uncertainty has arisen from the fact that functional requirement B4(1), which section 12 of Approved Document B was intended to support, requires only that the external walls should “adequately” resist the spread of fire, having regard to the height, use and position of the building. However, we assume that the word “adequately” was chosen to accommodate the full range of buildings to which the functional requirement applies. What is adequate will vary from case to case having regard to a number of matters, including the characteristics of the building.

It has been known for a long time that, even in the case of a fully compartmented residential building constructed entirely of non-combustible materials such as concrete (as Grenfell Tower was before the refurbishment), a fire in one compartment may spread to the compartment above as a result of the “coanda” effect. A limited degree of fire spread of that kind is not considered to undermine a stay put strategy because the extent of the evacuation required is very limited. Thus a limited degree of fire spread is acceptable, even where the building has a stay put strategy, because the ability of the external walls to resist the spread of fire is adequate.

However, the assumption underlying the guidance ceased to hold good when it became the practice to overclad high-rise residential buildings using materials that would support the spread of fire and to construct new buildings with steel frames with external walls composed in whole or in part of materials that would support the spread of fire. Unless all the materials used in the external wall are non-combustible, the effect in either case is to destroy the isolation of individual compartments by installing a continuous layer of combustible material on the outside of the building that would support the spread of fire across the outside of many compartments.

The failure to appreciate the effect of those developments introduced a fundamental flaw into the statutory guidance, which was not amended to draw the attention of designers to the need to consider the nature of the materials proposed to be used and other factors, such as access for the fire and rescue service, the nature of the occupants, the measures provided for alerting them to a fire and the means of escape if that should that become necessary, all of which have a bearing on whether the ability of the external wall to resist the spread of fire is adequate. If the external walls of a high-rise residential building support the spread of fire to any significant degree they are unlikely adequately to resist the spread of fire unless arrangements have been made to enable all those occupants who may be threatened by the fire to escape quickly and safely; but in any event it is not possible to operate a stay put strategy safely in relation to such a building.

The effect of the introduction of new materials and methods of construction does not appear to have been recognised by any of the witnesses (other than the experts), including those from DCLG or BRE.[28] There appears to have been a widely held view in the construction industry that if the surface of an external wall panel was classified Class 0, it was safe to use it on a building of any kind. There was also a widespread but erroneous understanding that if, following a test in accordance with BS 8414, an external wall system satisfied the criteria in BR 135, the building when completed would inevitably satisfy functional requirement B4(1) of the Building Regulations. Moreover, many in the industry failed to appreciate that the BS 8414 test applies only to a wall system as a whole and tells one nothing about its individual components. It is a matter of concern that no one appears to have considered whether the extent of flame spread that could occur while still satisfying the performance criteria in BR 135 was consistent with the adoption of a stay put strategy. We return to this matter in the context of our recommendations.

The second problem relates to the relationship between the regulations and the statutory guidance and the way in which Approved Document B is understood and applied by many in the construction industry. One striking feature of the evidence was the extent to which many construction professionals have routinely regarded the statutory guidance as containing a definitive statement of the requirements of the Building Regulations. In the absence of a clear statement to the contrary, we think that is an inevitable consequence of couching the guidance in prescriptive terms. Many construction professionals appear to be uncomfortable with the broad language of functional requirements B1 to B4 and want to be told what is expected of them and in any event many are not competent to translate the general language of the functional requirements into decisions about the choice of materials or methods of construction. That presents a particular problem for those who frame the statutory guidance, but while the functional requirements continue to set the standard which the law requires, it must be made clear in the guidance that following its provisions will not necessarily result in compliance with the regulations.

For reasons given elsewhere, Class 0 was never an appropriate standard for rainscreen panels, particularly panels with highly combustible polyethylene cores. In our view the guidance should explicitly have drawn the attention of those responsible for designing the cladding to the fact that Class 0 panels might not satisfy the requirements of functional requirement B4(1).

More generally, we think that Approved Document B requires a complete overhaul. It is out of date in many respects, not helpfully worded and does not contain the guidance that designers need. In a constantly changing environment it needs to be kept under review and revised annually or more often if circumstances demand. It should be drafted conservatively, so that those who follow the guidance can have a high degree of confidence that, if it is followed, the functional requirements will be met. Again, we return to this matter in the context of our recommendations.

In this chapter we describe the industry guidance relevant to the refurbishment of the external wall of Grenfell Tower that was publicly available from reputable sources at and around the time of the refurbishment. In addition to the guidance contained in Approved Document B, certain bodies within the construction industry published guidance on the various aspects of the construction of external walls, particularly the walls of high-rise buildings. There were important developments in that guidance, particularly between 2012 and 2017, as more became known about the performance of certain products and materials in response to fire. In some respects the guidance contained in Approved Document B was overtaken by guidance published by the industry which suggested more rigorous requirements for the fire performance of each element of any external wall. According to Dr Lane[29] and Mr Sakula,[30] knowledge of the dangers posed by the use of combustible materials was developing rapidly during that time, partly as the result of a series of fires in high-rise buildings in various countries whose external walls contained insulation made from organic materials and aluminium composite material rainscreen panels with a polyethylene core (“ACM PE panels”). Those fires and the information readily available about them are discussed in more detail in Chapter 11 of this report.

In 1988 the Building Research Establishment (BRE) published guidance entitled Fire performance of external thermal insulation for walls of multi-storey buildings.[31] It is generally known as “BR 135”. The document was revised in 1999 and a second edition was published in 2003 following the fire at Garnock Court, Irvine in 1999.[32] A third edition was published in 2013.[33] The second and third editions are relevant to the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower. BR 135 is expressly referred to in paragraph 12.5 of Approved Document B, which adopts its performance criteria using full scale test data derived from a BS 8414 test as providing one way of demonstrating compliance with functional requirement B4(1) of the Building Regulations.[34] The history of BR 135 and the test methods contained in BS 8414-1 (2002) and 2 (2005) are described in Chapter 5 of this report.

The second edition of BR 135 (2003) contained a series of important warnings about the risks posed by combustible external cladding systems. For example, Figure 2 illustrated the way in which fire may spread rapidly up through the building envelope itself to create secondary fires in compartments at many levels.[35]

The guidance contained further warnings about the risks posed by external cladding systems, in particular, the risk that the existence of cavities may cause flames to become elongated and drawn up the building, possibly unseen,[36] to affect several stories simultaneously and how fire can spread unseen through cavities,[37] thus making firefighting more difficult.[38] The guidance also referred to the fact that non-combustible materials were typically used in such systems as it was difficult to prevent fire entering the cavity and spreading through the insulating material.[39] It also warned that, if exposed directly to the sustained flame envelope, metal panels, such as aluminium, might melt, generating molten debris.[40]

The third edition of BR 135 (2013) repeated the warnings given in the second edition[41] and contained further warnings about external fire spread and the use of certain materials in cladding systems. In particular, it drew attention to the rapid development of the market for cladding systems, driven by the need to construct more energy-efficient and sustainable buildings, which had resulted in increased volumes of potentially combustible materials being used in external cladding applications.[42] There were further important warnings about the proper use of cavity barriers and fire-stopping. The warnings about insulation and cladding panels were also more detailed. In particular, on the subject of cladding panels it said:

“These products generally have good surface spread of flame characteristics to prevent rapid fire spread across the surface of the system, but once the panels become involved in the fire, they have the potential to generate falling debris, add to the overall fire load, and provide a route for fire to propagate up the outside of the building”[43]

The Building Control Alliance (‘BCA’) was formed in 2008 to represent the interests of those involved in carrying out building control functions, both local authorities and approved inspectors, and to promote consistency in the interpretation of the Building Regulations and statutory guidance. From time to time its Technical Group published guidance notes intended to assist building control officers in carrying out their functions.

In June 2014 BCA produced version 0 of its Technical Guidance Note 18 entitled Use of Combustible Cladding Materials on Residential Buildings (TGN 18).[44] The introduction to TGN 18 stated that the note outlined the procedures referred to in paragraph 12.5 of Approved Document B for demonstrating compliance with functional requirement B4(1) and set out to address common misconceptions relating to combustibility and surface spread of flame ratings.[45]

Under the heading “Key Issues”, TGN 18 stated that the spread of fire by way of the external wall is exacerbated by the use of combustible materials and extensive cavities. It warned that within the confines of a cavity, flames can elongate up to ten times in search of oxygen, meaning that there is a need for robust cavity barriers, restricted combustibility of key components and the use of materials with a low spread of flame rating.[46]

Importantly, TGN18 made it clear that a surface spread of flame classification does not indicate that the material is not combustible. It went on to state that:

“Thermosetting insulants (rigid polyurethane foam boards) do not meet the limited combustibility requirements of AD B2 Table A7 and so should not be accepted as meeting AD B2 paragraph 12.7. However, if they are included as part of a cladding system being tested to BR135 & BS8414, the complete assembly may ultimately prove to be acceptable.

The BR135 / BS8414 tests deal solely with the spread of fire once it has entered the cavity. Hence, the requirements for cavity barriers in accordance with Section 9 of AD B2 are required in all cases including around openings in the façade.”[47]

TGN 18 went on to recommend three options for demonstrating compliance with paragraph 12.7 of Approved Document B.[48] Option 1 was the use of materials of limited combustibility for all elements of the cladding system both above and below 18 metres. Option 2 was to demonstrate that the entire system met the performance criteria in BR 135 when tested in accordance with BS 8414. Option 3 was to submit a desktop study report from “a suitable independent UKAS accredited testing body” based on test data already in its possession stating whether, in its opinion, the proposed system would meet the criteria in BR 135. As far as we are aware, that was the first occasion on which it had been formally suggested that a desktop study could provide a means of demonstrating compliance with functional requirement B4(1). It was not referred to in Approved Document B and was not the method adopted in connection with the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower.

A further edition of TGN 18 (version 1) published in July 2015 contained similar warnings about external fire spread.[49] This revised guidance made it clear that a wider group of thermosetting insulants did not meet the limited combustibility requirements of Approved Document B Table A7, including polyisocyanurate and polystyrene foam boards. When dealing with desktop study reports the guidance now said that a report from a “suitably qualified fire specialist” based on test data from a suitable independent UKAS accredited testing body was acceptable, without indicating what qualifications might be required for the purpose. The effect of that change was to increase the number of persons who might be considered suitable to carry out such a study. This version also introduced a fourth option in the form of a “holistic fire-engineered approach” taking into account “the building geometry, ignition risk and factors restricting fire spread etc.”[50] That method was not adopted in connection with the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower.

The Centre for Windows and Cladding Technology (CWCT) is an industry body comprising a broad spectrum of clients, architects, consultants, contractors, manufacturers and researchers which exists to assist its members in the construction of building envelopes and glazing.[51] From time to time it publishes recommended standards and guidance for the benefit of its members and hosts meetings to discuss matters of interest to the industry. In the period 1996 to 2018, CWCT produced five documents of relevance to the Inquiry’s investigations: Guide to Good Practice for Facades, 1996;[52] Standard for Walls with Ventilated Rainscreens, 1998;[53] Standard for Systematised Building Envelopes, 2008 (“the CWCT Standard”);[54] Technical Note 73, Fire performance of curtain walls and rainscreens, March 2011;[55] and Technical Note 98, Fire performance of facades – Guide to the requirements of UK Building Regulations, 2017.[56]

The CWCT’s Guide to Good Practice for Facades (1996) stated that thermal insulation should be inert and drew attention to the fire performance of some insulating materials.[57] The Standard for Walls with Ventilated Rainscreens (1998) made clear that any cavity behind rainscreens should not include materials which could significantly promote flame spread within the unseen cavity and therefore recommended non-combustible insulation.[58] It warned that the use of any combustible material for the cladding framework and insulation needed to be carefully considered as the height of the building increased.[59] Both of those CWCT standards were referred to in the structural performance specification for Grenfell Tower.[60]

The CWCT Standard (2008) gave guidance on a range of aspects of the construction of the external envelopes of buildings[61], with part 6 focusing on fire performance.[62] Within part 6 the standard provided that the building envelope should not be composed of materials which readily support combustion, add significantly to the fire load, or give off toxic fumes.[63] It emphasised the importance of test evidence supporting fire performance requirements, as follows:

“In all cases, products or elements of construction requiring a fire resistance or spread of flame performance should have the appropriate evidence of performance test based on test information. The final installation should follow the applicable test evidence in all respects.”[64]

The CWCT Standard stated that aluminium envelope systems do not normally have significant resistance to fire and that most unmodified aluminium building envelopes would provide only 10–20 minutes stability and integrity resistance.[65] Under the heading “Insulation materials” it contained the same guidance as in paragraph 12.7 of Approved Document B, namely, that insulation in walls of buildings with a storey more than 18 metres above ground level should be of limited combustibility.[66] It also made clear that cavity barriers needed to be provided to close any cavity around penetrations through the rainscreen for windows.[67] The standard also expressly addressed “Composite components”, providing:

“When one of the cladding elements is a composite of two or more materials (mechanically jointed, bonded or fused together) the elements as a whole must demonstrate the appropriate fire performance. Similarly it must be demonstrated that the composite will remain reasonably whole and not become prematurely separated from the building or framework.”[68]

The CWCT Standard (2008) was expressly referred to in the NBS specification for the refurbishment works at Grenfell Tower (see Chapter 56).[69]

Technical Note 73, Fire performance of curtain walls and rainscreens, was published by CWCT in March 2011.[70] It contained warnings about fire and smoke spread within cavities and out of the top of cavities and highlighted the importance of cavity barriers to close the edges of cavities, including around window openings.[71] Under the heading “Use of combustible material” it made it clear that “the only commonly used insulation material that will satisfy the definition of limited combustibility is mineral wool”.[72] It also emphasised that where testing was carried out in accordance with BS 8414, the test applied to the complete cladding system including insulation, rainscreen and cavity barriers[73] and that changing any of those components might affect the ability of the walls to resist the spread of fire.[74]

Technical Note 98 Fire performance of facades – Guide to the requirements of UK Building Regulations was published in April 2017. Although it was published too late to be taken into account in the design and construction of the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower, it provides a useful picture of the state of knowledge in the industry in the months before the fire. In particular, in the introductory section the note warnsː

“Strict compliance with ADB does not necessarily guarantee adequate performance of a given façade in a fire. It is incumbent on the building designer to ensure that the guidance given in ADB is relevant to their building and what additional measures (if any) are required to ensure the façade achieves the required performance standard.”[75]

Technical Note 98 also stated that combustible materials may have non-combustible facings which restrict the spread of flame over the surface. It warned that combustible materials with non-combustible facings rely on the facings remaining intact and that the materials should be checked for damage.[76] Appendix C of Technical Note 98 dealt with the combustibility of materials and paragraph 12.7 of Approved Document B. It stated:

“Clause 12.7 specifically refers to insulation materials and filler materials but is now being interpreted more generally (see BCA Guidance note 18). Therefore, where a building has a storey 18m or more above ground level all significant materials should be of limited combustibility (Class A2 in accordance with EN 13501). This includes but is not limited toː

Rainscreen panels

Insulation materials

…”[77]

Booth Muirie Ltd is a company which provides specialist architectural cladding services, including design, manufacturing and distribution. In March 2016 it published a guide to designing multi-layered walls using ACM rainscreen panels.[78] Like the BCA Technical Guidance Notes it set out various options for complying with the fire safety requirements for external walls of buildings over 18 metres in height. Option 1, which was described as “the most straightforward” was to restrict all the significant elements of each layer to non-combustible materials or materials of limited combustibility. Options 2, 3 and 4 were the same as those contained in Issue 1 of the BCA’s TGN 18. Reynobond ACM with a polyethylene core, Celotex RS5000 and Kingspan K15 were all identified as being neither non-combustible nor of limited combustibility.

In this chapter we describe the organisations principally involved in the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower and the people who acted on their behalf. The purpose of doing so is to provide a brief introduction to those engaged on the project and the nature of their involvement. A number of other organisations, not referred to here, played minor and uncontroversial roles of a kind that do not call for discussion at this stage. Their involvement will be described in later chapters as we come to discuss particular aspects of the work.

The refurbishment of a major building is a complex undertaking which requires the co-operation of many different bodies, some with specialised skills and experience. In addition to the client, who ultimately controls the budget and determines the scope of the work, they usually include (and in this case did include) an architect, quantity surveyor, the principal building contractor and several sub-contractors. In this case other consultants were employed at different times and for different purposes. They included a mechanical and electrical services (“M & E”) consultant, a fire engineering consultant, an employer’s agent and a CDM co-ordinator. Others, such as the local authority building control office, were also directly involved in the project, although in a different way. Building control, in particular, had a responsibility to the public to ensure that those involved in the project complied with the requirements of the Building Regulations.

Although Grenfell Tower was owned by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), it was managed by the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (TMO) under a modular management agreement. Although the decision to refurbish the tower was taken by RBKC, which provided the funds required for that purpose, the TMO acted as the client and in that capacity procured the services needed to carry out the project and oversaw its execution. The circumstances in which the TMO procured the services of the architect and the main contractor are discussed in Chapters 51, 52 and 53.

As client the TMO also incurred certain obligations under the CDM Regulations 2007 and 2015. They included ensuring that all designers were competent and adequately resourced.[79]

The people principally involved in negotiating the contracts for the refurbishment on behalf of the TMO and overseeing the project were:

Mark Anderson

Peter Maddison

Paul Dunkerton

David Gibson

Claire Williams.

Mark Anderson was an architect by profession with experience of private practice before he became involved with social housing.[80] He was appointed by the TMO as interim Director of Asset Investment and Engineering in March 2011 and following a redesignation of his role served as interim Director of Assets and Regeneration from April 2012 until January 2013.[81] He was responsible for the early stages of the refurbishment project which he later handed over to Peter Maddison when the latter was appointed to succeed him.

Peter Maddison was appointed by the TMO to the post of Director of Assets and Regeneration from January 2013.[82] In that role he took over primary responsibility for organising the refurbishment project at a strategic level for the TMO, including overseeing the engagement of consultants and the selection of the main contractor.

Paul Dunkerton was a freelance project manager for the TMO between late 2010 and early July 2013.[83] He initially reported to Mark Anderson and later to Peter Maddison, taking on a more active role when he had no senior manager to whom to report.[84]

David Gibson was Head of Capital Investment at the TMO from February 2013 until the end of June 2016, reporting to Peter Maddison.[85] As such he was responsible for assisting Mr Maddison in the development and delivery of the refurbishment project. Mr Gibson had been a registered architect between 1987 and 1991 and had had some previous experience of regeneration projects in the social housing sector.[86]

Claire Williams joined the TMO in September 2013 as project manager for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment. Once the work began, she became the primary point of contact with the main contractor. One of her tasks was to communicate with the residents of Grenfell Tower,[87] having been appointed for her particular skill and experience in resident relations.[88] She considered herself to be the TMO’s project manager for the refurbishment,[89] although there was some confusion about who, if anyone, was formally acting in that capacity.

The architectural practice known as “Studio E” was appointed by the TMO for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment and provided professional services in respect of the project from about February 2012 to July 2016.[90] In Chapter 52 we describe the circumstances in which it came to be appointed, but for present purposes it is necessary to refer in a little more detail to the origin and structure of the practice.

Studio E Architects Limited (“SEAL”) was founded in 1994 by Andrzej Kuszell and two others. A separate body in the form of a limited partnership, Studio E LLP (“SELLP”), was established by Mr Kuszell and his partners in 2007 but did not start trading until 2011.[91] Thereafter, between 2011 and 2014, SEAL was effectively dormant[92] but it was revived in 2014 when SELLP became insolvent and ceased trading. Throughout this report we refer to the practice simply as “Studio E”, except when it is necessary to identify the particular legal entity involved.

After the principal contractor had been appointed Studio E’s services were transferred to it under a separate agreement between them. We discuss the circumstances under which that occurred and the terms of the resulting contractual arrangements in Chapter 63.

Studio E was represented in relation to its work on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment principally by the following persons:[93]

Andrzej Kuszell

Bruce Sounes

Neil Crawford

Tomas Rek.

Andrzej Kuszell is a registered architect and a founding director of SEAL.[94] During his career he worked in various sectors, including defence, commercial development and education work with an emphasis on education, sports and leisure centres.[95] Mr Kuszell did not have day-to-day involvement with the Grenfell Tower project,[96] although he oversaw the provision of resources and took part in design reviews. He did not have any personal experience of overcladding an occupied residential building and no personal experience of refurbishing a high-rise building.[97]

Bruce Sounes studied architecture at the University of Natal at Durban in South Africa between 1989 and 1994. He completed the RIBA Part 3 examination and became a registered architect in 2000.[98] Before 2000, his experience had been predominantly in education, sports, and leisure projects.[99] He joined Studio E in the role of architect in 2000 and was promoted to the role of associate in 2005.[100] Mr Kuszell said that it was not unusual for an associate to lead a project and that for a commission with a construction value of £1 million or more either a partner or an associate would do so.[101] From July 2014, Neil Crawford took over day-to-day responsibility for the project from Mr Sounes, although Mr Sounes remained responsible for it and for supervising Mr Crawford’s work.[102] Mr Sounes did not have any experience of overcladding an occupied residential building, although he had gained some experience of an overcladding project when working on the Watford Woodside Leisure Centre.[103]

Neil Crawford had a degree and a post-graduate diploma in architecture[104] but was not a registered architect because he had not completed the Royal Institute of British Architects Part 3 examination.[105] Between 1997 and 2009 he had worked at Foster + Partners, initially as a Part 2 graduate and later as an associate.[106] He joined Studio E in 2009 and soon became an associate.[107] From July 2014, he took over day-to-day responsibility for the project from Mr Sounes, although Mr Sounes continued to lead it.[108]

Mr Crawford worked on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment on a day-to-day basis.[109] By October 2015, he had been made the project architect.[110] He had some limited experience of commercial projects involving cladding and curtain walling but had not previously been involved in the overcladding of a high-rise residential building.[111]

Tomas Rek was a registered architect who was employed by Studio E between December 2011 and December 2013.[112] Before joining Studio E he had worked mainly in the education sector.[113] He started work on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment project on 18 September 2013.[114] Under the supervision of Mr Sounes, he developed the National Building Specification (NBS) specification for the project and the architectural drawings intended to form part of the tender documents.[115] (The NBS is a computerised system designed to assist architects and other building professionals in describing the materials, standards and workmanship required on a construction project.) Studio E drafted three versions of the NBS Specification dated 21 November 2013[116], 29 November 2013[117] and 30 January 2014.[118] The second and third of those were sent to tenderers.

Appleyards Ltd had been appointed by the TMO as a consultant on the KALC project and as a result the TMO appointed it as quantity surveyor, employer’s agent and CDM co-ordinator for the Grenfell Tower project. In March 2012, Artelia Ltd bought Appleyards and thereafter Appleyards traded in the name of Artelia until 30 June 2015, when its business was formally transferred to Artelia.[119] In this report we refer to both entities as Artelia, unless the context requires otherwise.

A quantity surveyor is a surveyor trained in the particular skill of calculating the quantity and cost of materials required to carry out, or that have been used in carrying out, the whole or a particular part of a construction project. They may be used to estimate the cost of work, help manage costs during the course of the work and participate in agreeing the final account.[120] Artelia agreed to provide quantity surveying services, including preparing an initial budget to test feasibility, preparing regular monthly cost reports as the project progressed and advising the TMO of any decisions required.[121] Simon Cash was its project director and had overall responsibility for the whole of Artelia’s involvement in the refurbishment.[122] He was a trained quantity surveyor and a Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.[123]

The function of an employer’s agent is to perform on behalf of the client various administrative tasks that have to be undertaken by it in relation to a project.[124] Philip Booth acted as employer’s agent from about April 2013 until June 2015.[125] He left Artelia in April 2016.[126] Neil Reed succeeded Philip Booth as employer’s agent in March 2015.[127] In July 2015, Neil Reed left Artelia to start his own business, Re Sol Group Limited (Re Sol), but continued to provide the services of employer’s agent under a subcontract with Artelia.[128]

CDM co-ordinator (CDM-C) is a statutory role under the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2007 (“CDM Regulations 2007”).[129] The regulations required the TMO to appoint a CDM co-ordinator (CDM-C) for the Grenfell Tower project because of its size.[130] The CDM-C is required to assist and advise the client on the appointment of competent contractors, ensure that health and safety matters are properly co-ordinated during the design process, help communication and co-operation between project team members and prepare the health and safety file.[131] Keith Bushell of Artelia was appointed to that role. Following the introduction of the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 (CDM Regulations 2015), Artelia’s appointment as CDM-C terminated on 6 October 2015. On 8 October 2015, Simon Cash wrote to Peter Maddison to confirm that Artelia’s appointment as CDM-C had terminated.[132]

The TMO appointed Max Fordham LLP as building services engineers with effect from the summer of 2012. Andrew McQuatt was the lead project engineer.[133] Matt Cross Smith was a building services engineer who worked on the Grenfell Tower project as a graduate engineer.[134]

Curtins Consulting Limited (Curtins) was the consultant structural engineer for the Grenfell Tower project. Its contract was novated to Rydon by an agreement dated 25 April 2016 following that company’s appointment as principal contractor.[135]

Exova (UK) Ltd, trading as Exova Warringtonfire (Exova), is a company specialising in fire safety, fire engineering and related matters. It had been employed as a consultant by Studio E in connection with the KALC project,[136] and as a result, it was approached by the TMO to advise on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment.[137] Although it was retained by the TMO, it continued to send reports to Studio E.[138] There was no fresh tender or procurement exercise for fire engineering services for the Grenfell Tower project. Exova was used because it was known and trusted as a result of its work on the KALC project.

The TMO appointed Exova to produce a fire safety strategy for Grenfell Tower in its existing state (the “Existing Fire Safety Strategy”)[139] and a fire safety strategy for the building in its refurbished condition (the “Outline Fire Safety Strategy”).[140] Its appointment was not novated to Rydon after that company had been appointed as principal contractor and it therefore continued as a consultant to the TMO.[141] However, as discussed in Chapter 54, there was a confusion in some people’s minds about Exova’s position following Rydon’s appointment that was never properly clarified.

In relation to its work on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment Exova was represented principally by the following persons:

James Lee

Cate Cooney

Dr Clare Barker

Terence Ashton

Dr Tony Pearson.

For a brief period, James Lee was involved with the project until he left the company in late July 2012. He attended a design team meeting on 19 April 2012[142] and visited the tower briefly on 29 May 2012.[143] He provided Studio E with a series of marked-up drawings and comments in respect of the proposed refurbishment works[144] and prepared a fee proposal for Studio E for the production of the Existing Fire Safety Strategy.[145]

At the time Exova was appointed Dr Clare Barker was a principal fire engineer in Exova’s Warrington office and a member of the Institute of Fire Engineers.[146] She attended a project meeting on 26 July 2012,[147] shortly before Exova was instructed to provide the Existing Fire Safety Strategy. She asked another employee, Cate Cooney, to prepare a first draft,[148] which she later reviewed.[149]

Cate Cooney had joined Exova in 2011 after spending eight years working in building control. By 2012 she had reached the position of senior consultant. At the request of Dr Barker, she prepared the first draft of the Existing Fire Safety Strategy. She also provided some advice to Bruce Sounes of Studio E in relation to the refurbishment proposals.[150]

Terence Ashton had joined Exova in 1989 as a principal consultant after 25 years in building control. He was based at Exova’s London office, where he was an associate in the fire engineering department[151] and acted as office manager.[152] He had no formal qualifications in fire engineering. He had worked on high-rise residential buildings but had no experience of overcladding projects.[153] He did not have the expertise to carry out highly technical fire engineering analyses, such as determining how particular materials are likely to behave in a fire, and would have called on his colleagues in Warrington for assistance if had he been asked to do one.[154] He saw his primary role as being to ensure compliance with the Building Regulations.[155] Following James Lee’s departure from the company in July 2012, Terence Ashton assumed overall responsibility for Exova’s work on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment.

In 2013, Mr Ashton was aware that Approved Document B contained an express warning that the use of combustible materials in cladding systems and the existence of extensive cavities might present a risk to health and safety in tall buildings.[156] Although he was aware of the existence of BR 135, he had not read it from cover to cover and it did not occur to him to read it before starting work on the Grenfell Tower project.[157] Mr Ashton was aware that serious fires had occurred both in the UK and overseas as a result of the use of inappropriate materials (although he was not aware of the fire at the Lacrosse Building in Melbourne) and was therefore aware that combustible cladding should not be used on high-rise buildings.[158] He had not encountered the use of composite metal panels, apart from one particular composite panel with a polyethylene core.[159] However, he did not envisage that material of that kind would be used on high-rise buildings. He knew that polyethylene was a highly combustible substance and was aware, at least subconsciously, that panels containing polyethylene could exacerbate the spread of fire over the exterior wall of a building.[160]

Dr Tony Pearson joined Exova in 2008 as a graduate. In 2013 he was promoted to senior consultant[161] and remained in that role until he left the company in January 2016.[162] Before he started working on the Grenfell Tower project Dr Pearson had had no experience of refurbishing high-rise residential buildings and very little experience of overcladding projects.[163]

The TMO engaged John Rowan & Partners to provide a limited range of clerk of works services during the refurbishment. John Rowan is a construction consultancy offering a variety of services to the construction industry, including site monitoring and supervision or clerk of works services.[164] Those principally involved were Gurpal Virdee, the managing partner since August 2016,[165] and Jonathan (“Jon”) White, who was an experienced clerk of works.

The functions that John Rowan were required to perform were more limited than those that would be performed by a traditional clerk of works.[166] In effect, they were employed to act as site inspectors or site monitors[167] and were expected to focus a lot of attention on the residents.[168]

The TMO appointed Rydon Maintenance Ltd (“Rydon”) as principal contractor under a contract on the JCT Design and Build Contract form 2011 with amendments.[169] As principal contractor, Rydon was responsible for all aspects of the refurbishment project, including its design, compliance with the Building Regulations and other statutory requirements. The refurbishment division of Rydon, led by its Refurbishment Director, Stephen Blake, was responsible for the project. We describe the circumstances in which Rydon came to be appointed in Chapter 53.

Those principally involved in the refurbishment on behalf of Rydon were:

Stephen Blake, the Refurbishment Director

Simon Lawrence, one of the contract managers

Simon O’Connor, a project manager

David Hughes, a site manager

Gary Martin, a site manager

Daniel Osgood, a site manager

Zak Maynard, the commercial manager.

Stephen Blake was Refurbishment Director throughout the project.[170] He assumed the role of contract manager in October 2015 following the departure of Simon Lawrence to see the project through to completion and was the most senior Rydon employee to be directly involved in the Grenfell Tower refurbishment.[171]

Simon Lawrence was the contracts manager responsible for the refurbishment from its inception until October 2015. As such he was the most senior Rydon employee with day-to-day involvement in and responsibility for the project.[172] When he left Rydon in 2015 Stephen Blake took over his role.

Simon O’Connor was project manager for the refurbishment until September 2015.[173] He had worked for Rydon since September 2002, progressing from foreman to site manager and then to project manager.[174] The Grenfell Tower refurbishment was the first project for which he had taken on the role of project manager.[175] It was his task to manage the day-to-day running of the project on site.[176]

David Hughes was employed by Rydon as a site manager for the Grenfell Tower project from October 2015 until its completion.[177] He had worked for Rydon since November 2001, after graduating with a degree in civil engineering from Plymouth University.[178]

Gary Martin was employed by Rydon as a site manager on the Grenfell Tower project from May 2014 until its completion. Before joining Rydon he had worked for another company as a site manager on residential refurbishment projects.[179]

Daniel Osgood had joined Rydon in March 2014, starting in the role of temporary site manager.[180] He was employed by Rydon as a site manager on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment from April 2015 until July 2015, when he was moved to work on a different project.[181] At the time of the Grenfell Tower project, he had worked as a site manager for over 10 years.[182]

Zak Maynard was Rydon’s commercial manager, responsible for all financial aspects of the project,[183] including the management of a team of several surveyors, the allocation of work packages to subcontractors, controlling budgets, assessing the financial implications of changes to the works and liaison with the employer’s agent.[184]

Although it took responsibility for all aspects of the design and execution of the works, Rydon did not employ within its organisation people with all the skills and expertise required to discharge its contractual obligations. As is common in the construction industry, it preferred to delegate the discharge of its responsibilities to a host of subcontractors, regarding itself as little more than the conductor of a large and varied orchestra of players. Later in the report we shall refer to the following subcontractors who were employed by Rydon on the refurbishment:

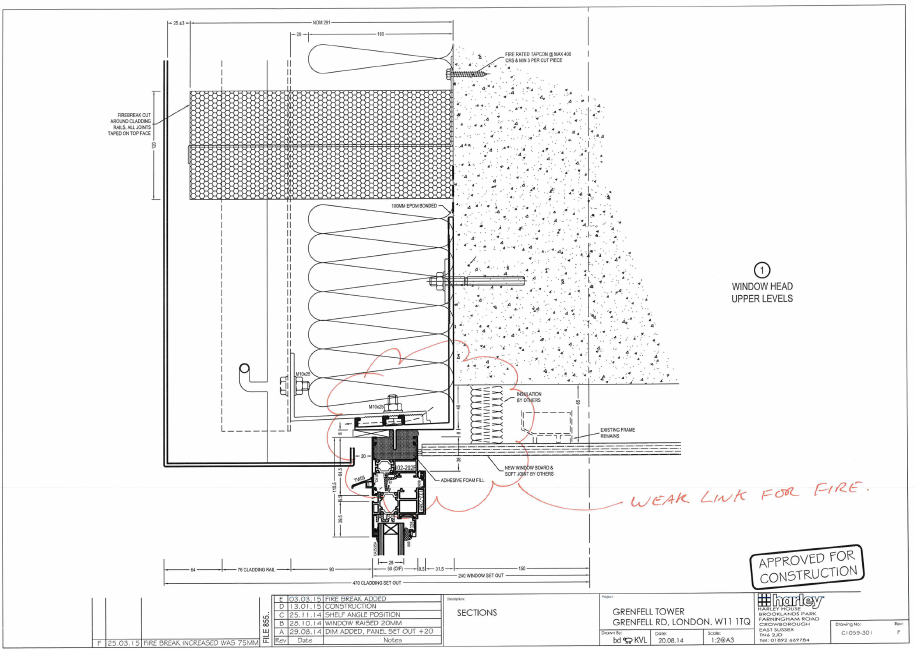

Harley Curtain Wall and Harley Facades

J S Wright & Co Ltd

S D Plastering Ltd

S D Carpentry Ltd.

Harley Curtain Wall (“Harley CW”) was established in 1996 by Ray Bailey to carry on the business of designing and installing facades of buildings under construction. By 2013, Harley employed about 16 people,[185] but none of them had any formal qualifications in facade engineering.[186] Mr Bailey had been involved in several projects on high-rise residential buildings which had used ACM rainscreen panels before Harley undertook the work on Grenfell Tower.[187] It was Harley’s practice to subcontract much of the work it undertook, including design, manufacture and the installation of the facade itself.[188]

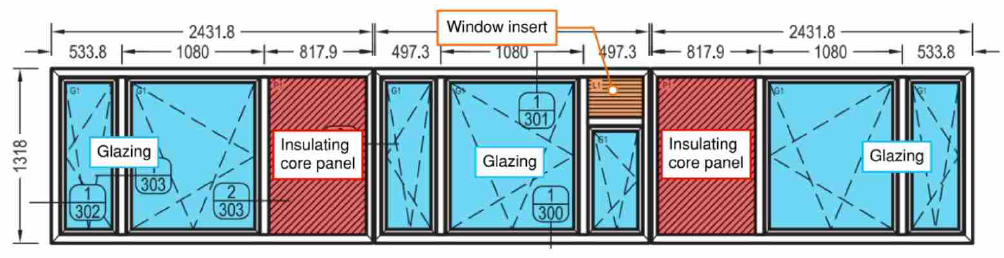

Harley Facades was established in 2000, also by Ray Bailey. He had originally intended to use the two Harley companies on separate projects,[189] but in the event Harley Facades remained dormant until 2015 when Harley CW went into administration. At that point it took over the work on the Grenfell Tower project.[190] In Chapter 65 we describe how Harley came to be appointed and the key terms of its contract with Rydon. For present purposes it is sufficient to say that Harley was contractually responsible to Rydon for all aspects of the design and construction of the facade of Grenfell Tower, including the cladding, insulation, window frames, window infill panels, glazing and cavity barriers.

The people principally involved in the project on behalf of Harley were:

Ray Bailey

Mark Harris

Mike Albiston

Daniel Anketell-Jones

Ben Bailey.

Ray Bailey was the founder of the Harley companies and was in overall control of the business. Mr Bailey graduated with a degree in civil engineering from Salford University in 1981 following which he worked for a number of companies in which he gained experience of all aspects of building envelopes, including design, manufacturing and installation.[191] He had no formal qualifications in facade engineering.[192]

Mark Harris was a self-employed consultant in the field of commercial glazing and cladding appointed by Harley to assist with the Grenfell Tower project.[193] He had been working exclusively for Harley since about 2011 and his experience lay mainly in the field of sales and developing business connections.[194] By the time he became involved in the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower Mark Harris had been involved in several projects on which ACM panels had been used.[195]

Mike Albiston was Harley’s senior estimator for the Grenfell Tower project. His main contribution was assisting in the production of Harley’s tender for the work of designing and constructing the facade, which began in December 2013.[196]

Daniel Anketell-Jones had been engaged by Harley as a project engineer in November 2006[197] and had been promoted to the role of design manager by the time Harley began work on the Grenfell Tower project.[198] His main duties were to appoint a designer and monitor the progress of the design work until a project manager had been appointed. Between 2014 and 2017, while employed by Harley, he obtained an MSc in structural engineering and began studying for an MSc in facade engineering,[199] but he had not received any instruction in the fire performance of facades until after he had left Harley and his involvement in the Grenfell project had come to an end.[200] During his time at Harley Daniel Anketell-Jones had been involved in a design capacity in two previous high-rise overcladding projects.[201] While working on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment he also worked on two other Harley projects.[202]

Ben Bailey is the son of Ray Bailey. He was employed by Harley as project manager for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment but had not been involved in that capacity on any previous project.[203] He had worked for Harley from time to time while at school and university and had been taken on as a site manager following his graduation in 2013.[204] Until about May 2017, Ben Bailey continued to be involved intermittently in the Grenfell Tower project when maintenance requests or problems with snagging required attention.[205] When he started work on the Grenfell Tower project Ben Bailey had no previous experience of managing the refurbishment of a high-rise residential building.[206]

Harley engaged the following as sub-contractors:

Kevin Lamb, to produce designs and construction drawings

CEP Architectural Facades Ltd, to fabricate and supply ACM rainscreen cassette panels

Osborne Berry Installations Ltd, to install the cladding.

Kevin Lamb was a self-employed designer of curtain walling and cladding, including glazing and rainscreen systems. He was engaged by Harley for the Grenfell Tower project in August 2014,[207] having previously worked for it on one other project as a freelance draftsman.[208] Mr Lamb had previously produced preliminary schematic drawings for the Chalcots Estate refurbishment undertaken by Harley.[209]

CEP Architectural Facades Ltd (CEP) was appointed by Harley as a subcontractor to fabricate and supply the rainscreen panels and glazing units for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment. Geof Blades was a director from 2004 until 2013, when CEP was sold.[210] After that, he remained with the company as national glazing manager until 2016, when he became commercial projects manager. He retired in 2018.

CEP entered into six contracts with Harley between October 2014 and November 2015 for the fabrication and supply of rainscreen cladding panels and window units for Grenfell Tower.[211] In addition, after Harley Curtain Wall had gone into administration, in September 2015 CEP entered into a contract with Rydon for the supply of Reynobond PE 55 panels.[212]

Osborne Berry Installations Ltd was established by Mark Osborne and Grahame Berry in 2002 as a corporate vehicle for their business of installing windows and cladding on buildings under construction or in the course of refurbishment.[213] Osborne Berry had worked for Harley on many previous occasions and was engaged by Harley to install the facade, including the windows, cavity barriers, cavity wall insulation and the rainscreen panels.[214] The company engaged self-employed fitters to carry out the work.

There was no written contract between Harley and Osborne Berry[215] and no document exists which sets out the terms on which Osborne Berry was engaged to carry out the work, the scope and content of that work, the standard to be applied or any programme for the works. Grahame Berry said that there may have been some conversations with Ray Bailey about a programme of works, but not about the quality or the standard of workmanship.[216] Ray Bailey said that it was not uncommon for Harley to appoint subcontractors without any written contract.[217]

SD Plastering Limited (SDP) was incorporated in 2002. It was a company that mainly provided dry-lining services.[218] Rydon sub-contracted a package of work to SDP, most of which comprised dry-lining, plastering, remodelling and ceiling works to the lower floors of the tower.[219] In about February 2015, Rydon asked SDP to assist in designing the internal window linings and to carry out the work on the refurbishment of the internal window reveals.[220] Rydon subsequently sub-contracted the work on the internal window reveals of the newly refurbished windows to SDP.[221]

Rydon employed J S Wright & Co Ltd to carry out the mechanical and electrical works which included the design and supply of a new smoke control and ventilation system for Grenfell Tower. J S Wright employed PSB UK Limited to design and install the smoke control and ventilation system.

Building control functions were carried out by RBKC’s building control department. John Allen had joined RBKC as an assistant district surveyor in 1996. By the time he became involved in the refurbishment in 2012, he was Head of Special Projects and was subsequently promoted to Building Control Manager in September 2013.[222] He was directly involved in giving advice on the refurbishment in 2012 and 2013 before any application had been submitted. John Hoban took over responsibility for Grenfell Tower in about December 2013.[223] Between 2014 and 2016 as Mr Hoban’s manager Mr Allen continued to be involved in the refurbishment and in due course the completion certificate for the refurbishment was issued in his name as Head of Building Control.[224]

John Hoban was a senior surveyor in RBKC’s building control department between 1986 and March 2017, when he retired.[225] He holds BTEC ordinary and higher certificates in building studies. He worked as a junior technical officer in the Building Regulations division and from 1979 to 1986 as a technical assistant in the District Surveyor’s office of the Greater London Council.[226] At the time of the refurbishment he was an associate member of the Chartered Association of Building Engineers.[227] The refurbishment was the first project on which he had to deal with the overcladding of an occupied high-rise residential building.[228]

Paul Hanson was a senior building control surveyor (Fire Regulations) who acted as a consultant to the building control surveyors.

Jose Anon joined the building control department as a surveyor in 1989.[229] In 2013 he was promoted to Deputy Building Control Manager.[230] He was not involved in the refurbishment, save for one site visit on 17 April 2015.[231]

In this chapter we describe the background to the Grenfell Tower refurbishment project, including its origins and reasons, the establishment of the project team and the appointment of Studio E as architect.